'I'm not an enemy': Moscow exhibit showcases Gulag letters

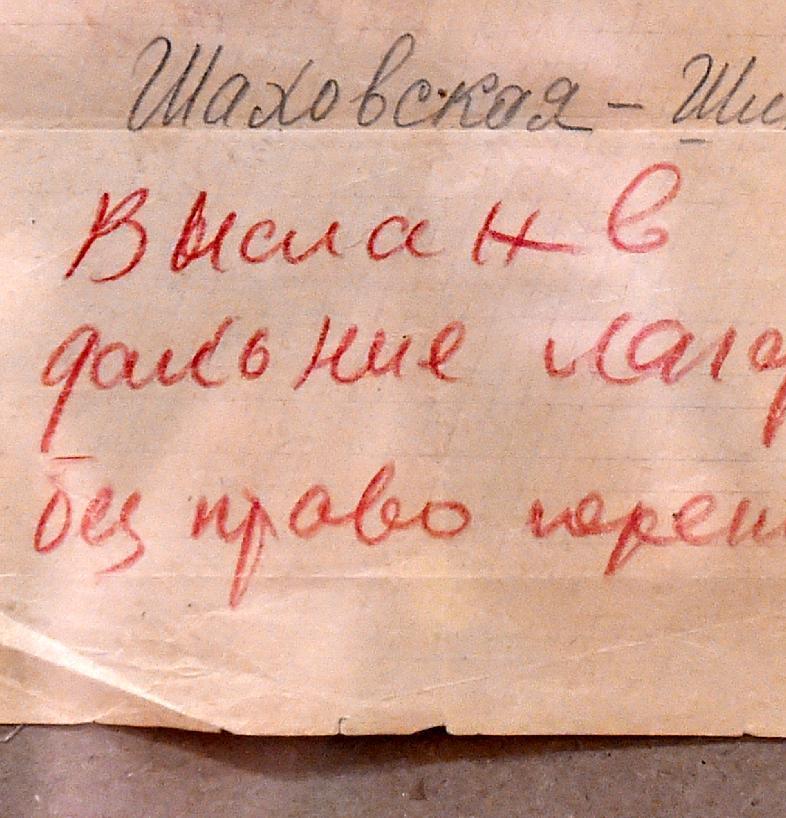

Written on cigarette packs or scraps of newspaper, embroidered with a fishbone on shreds of cloth or scratched on birch bark, clandestine letters from the Soviet Gulag were composed by any means prisoners had. Now those desperate calls from people banished to the oblivion of Soviet-era labour camps are being given full voice in a Moscow exhibition showcasing letters from the Gulag. Entitled “The Right of Correspondence,” the exhibition is organised by Russia’s top rights group, Memorial, and displays hundreds of letters sent by Gulag inmates to their families. It runs to May 4. The letters illustrate the history of the network of Soviet labour camps from its creation in the 1930s up to the 1980s.

Dear Dad and Mum, I don’t know where I am being taken to. I am sentenced to 10 years in camp.

Poet Vasily Malagusha, while en route to the Kolyma labour camp in Russia’s Far East in 1938

Gulag prisoners could be granted correspondence rights of one letter a month, one every six months or once a year. But withdrawing that privilege was a favoured means by authorities to punish inmates, many of whom had to resort to various tricks to circumvent the ban.Their letters were often folded in the form of a paper aeroplane and flown over the barbed wire, where passers-by could pick them up and post them to indicated addresses — but at the risk of losing their own freedom. “Most of them were written in 1937 and 1938 –- at the height of Stalin’s purges, when 700,000 ‘enemies of the people’ were executed,” said Irina Ostrovskaya, the exhibition’s curator.

Correspondence was the only connection to life for Gulag prisoners.

Arseny Roginsky, president of Memorial, which documents Russia’s Soviet totalitarian past

Arts