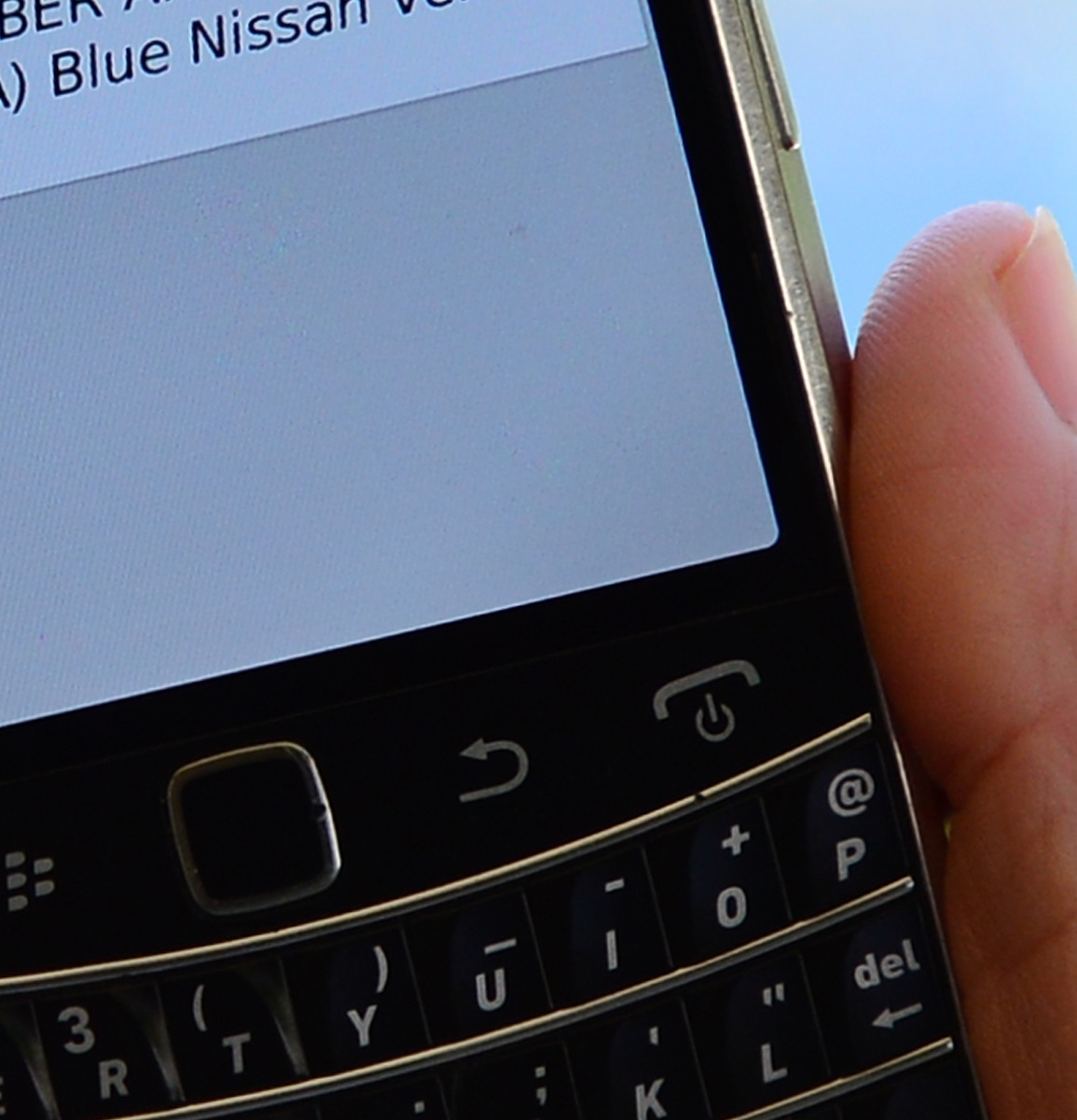

Unwarranted? Canada’s top court rules police can search cellphones in arrests

A divided Supreme Court of Canada has ruled that police can conduct a limited search of suspect’s cellphone without getting a search warrant, but they must follow strict rules. By a 4-3 margin, the court said in a precedent-setting ruling that the search must be directly related to the circumstances of a person’s arrest and the police must keep detailed records of the search. Three dissenting justices said the police must get a search warrant in all cases except in rare instances where there is a danger to the public or the police, or if evidence could be destroyed. It is the first Supreme Court ruling on cellphone privacy, an issue that has spawned a series of divergent lower court rulings, and in writing for the majority, Justice Thomas Cromwell said the court was trying to strike a balance between the demands of effective law enforcement and the public’s right to be free of unreasonable searches and seizures under Section 8 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

In my view, we can achieve that balance with a rule that permits searches of cellphones incident to arrest, provided that the search — both what is searched and how it is searched — is strictly incidental to the arrest and that the police keep detailed notes of what has been searched and why.

Justice Thomas Cromwell of the Supreme Court of Canada

The high court dismissed the appeal of the 2009 armed robbery conviction of Kevin Fearon, who argued unsuccessfully that police violated his charter rights when they searched his cellphone without a warrant after he’d robbed a Toronto jewelry kiosk. The court agreed that the police had in fact breached Fearon’s rights, but the evidence against him on his cellphone should not be excluded. Writing for the three dissenters, Justice Andromache Karakatsanis said police should need a warrant in all cases to search a cellphone, adding that the court’s majority ruling had proposed an “overly complicated template” for police to follow. In June, the U.S. Supreme Court rules that police in that country do need a warrant in order to search cellphones.

I doubt not that police officers faced with this decision would act in good faith, but I do not think that they are in the best position to determine ‘with great circumspection’ whether the law enforcement objectives clearly outweigh the potentially significant intrusion on privacy in the search of a personal cellphone or computer.

Justice Andromache Karakatsanis wrote for the dissenters

Americas